The other day we started asking what the gospel writers actually thought about the gospels they were writing. We saw that Mark was interested in how Jesus’ story brings Israel through its anticipated new exodus. We saw that Matthew, similarly, believed Jesus to be (1) the fulfillment of the promise to Abraham, (2) the successor to David with an everlasting kingdom, and (3) the one to bring Israel out of its long exile.

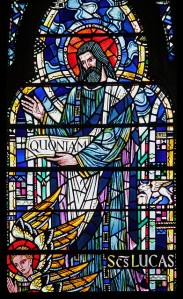

We move now to Luke. What did he suppose the gospel was all about?

Looking at Luke’s introduction, as we did with Matthew and Mark, we notice right away that Luke begins differently. His introduction doesn’t have Mark’s handy little epigraph. Nor does he begin with a lengthy genealogy that stands apart from the rest of the narrative. (Luke does have his own genealogy for Jesus—with its own purposes—but it doesn’t come until chapter 3.) Luke’s introduction is actually a greeting to his intended audience (Lk 1:1-4), and in that greeting he gives no indication concerning themes that will appear throughout the text.

In fact, to find the themes that concern Luke up front, we have to let his storytelling do its work on us. And it’s not even about reading between the lines, as it might have been with Mark and Matthew, because Luke’s emphasis comes to us about as plainly as could be as the opening chapters unfold.

The story opens not with Jesus himself, not even, really, with John the Baptist, as in Mark, but with John’s parents, Zechariah and Elizabeth. Elizabeth is barren and Zechariah works in the Temple. Big Z gets a visit from the angel Gabriel in the Holy of Holies and is told that they will indeed have a son, whose name will be John. Their son, further, will be the one of whom Malachi spoke, the one who precedes the dramatic Day of the Lord (cf. Lk 1:17; Mal 4:5-6).

We saw this theme already in Mark and in Matthew both. They all see Jesus’ story as completing the long exile of God’s people. They’re coming home, we might say, and God is on his way, as well.

Then, of course, Jesus’ birth is foretold to Mary, and, just as with Zechariah, Gabriel is not shy about pronouncing her miracle boy’s purpose: “He will be great and will be called Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever; his kingdom will never end” (Lk 1:32-33, TNIV).

Many have read the first portion of this prophecy and decided Gabriel meant to tell Mary that her son would be God. And then they have ready the second portion and decided that this was an additional kingly portion. But this is not Gabriel’s intention. Rather, Gabriel is saying the same thing several times over in these two verses. All of it, as we saw with Matthew’s citation of David, comes from 2 Samuel 7.

Notice the relevant passage, with emphases to show Luke’s parallels:

The Lord declares to you that the Lord himself will establish a house for you: When your days are over and you rest with your ancestors, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, who will come from your own body, and I will establish his kingdom. He is the one who will build a house for my Name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. I will be his father, and he will be my son. When he does wrong, I will punish him with a rod wielded by human beings, with floggings inflicted by human hands. But my love will never be taken away from him, as I took it away from Saul, whom I removed from before you. Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever (2 Sam 7:11b-16).

Gabriel has made the announcement that Jesus will be the son of David, for whom Israel has been waiting a thousand years.

Luke’s story goes on. Mary rushes off to visit her cousin Elizabeth and is so moved by the experience, she bursts into song. Whether Luke saw himself as the predecessor for Rogers and Hammerstein, with the incessant urge to insert musical numbers every so often in the narrative, I don’t know. What I do know, however, is that Luke is drawing heavily from Hannah’s prayer in 1 Samuel 2.

The sum total of Luke’s opening chapter paints a daring picture, one that no one familiar with the Hebrew Scriptures could miss. The Old Testament story in question begins with the barren Hannah crying out to the Lord for a child. Her child becomes a prophet whose career culminates with the anointing and ascension of David, the truest king from Israel’s history, a man after God’s own heart.

Luke condenses the tale: the childless Elizabeth gives birth to a prophet who will be the forerunner to a new and greater David, whose kingdom will never cease. The rise of a new kingdom—that’s the gospel Luke is telling.

In Luke’s account of the crucifixion, Jesus hangs from the cross between two common criminals (Lk 23:32-33). Jesus hangs there with them, as a convicted criminal just as they are. Indeed Jesus hangs indicted as an enemy of the state. An empire whose Caesar rules the known world cannot have a rival king within its territories. The King of the Jews had to be dealt with severely.

In Luke’s account of the crucifixion, Jesus hangs from the cross between two common criminals (Lk 23:32-33). Jesus hangs there with them, as a convicted criminal just as they are. Indeed Jesus hangs indicted as an enemy of the state. An empire whose Caesar rules the known world cannot have a rival king within its territories. The King of the Jews had to be dealt with severely.